The Israeli Center for Citizen Science, based at the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History at Tel Aviv University, aims to be the national hub for citizen science and biodiversity monitoring in Israel. Alongside technological, scientific, and social infrastructure, the Center plans to provide guidance and support to citizen science initiatives based on available resources. To this end, several pilot projects were conducted, their implementation analyzed, and insights gathered. We presented the findings from 19 years of the Great Bird Count at the European Citizen Science Association conference in April 2024.

The Bird Count has been running in Israel since 2006, inspired by similar projects worldwide. The public is invited to go out into their backyards and nearby gardens during a specific month (around January) and report on bird species and counts via the eBird app following a structured protocol. The project has three goals:

Scientific – build a long-term database of wild bird species and characterize trends and frequency changes over the years.

Community engagement – increase public involvement in nature conservation.

Educational – raise awareness and familiarity with local birds, deepen knowledge, and promote active citizenship.

Over the years, the bird count evolved in several aspects: leadership teams, data collection protocols, count durations, reporting technology, and outreach efforts to the general public and educators. The project has tracked changes in urban bird biodiversity, increased public engagement, and integrated into educational systems over time.

Changes Across Project Phases

Our review of the changes made throughout the life of the Bird Count project offers valuable insights into the lifecycle of citizen science initiatives, and how to maintain a dynamic project environment in the face of cultural and technological developments. Our study identified three key phases in the life of the project, during which changes occurred across four main dimensions: leadership, data collection protocols, reporting processes, and data analysis.

Phase 1 (2006–2015)

Initiated by amateur birdwatchers from the “Wild Birds in Gardens and Yards” group, inviting the public to count birds near their homes during a month in January. Reports were submitted via mail, email, or fax. Protocols asked participants to count all birds seen within a 50 m radius over 15–30 minutes. Data was processed in Excel and detailed reports were mailed to participants and published on the Center’s site.

Phase 2 (2016–2021)

The Israel Nature and Parks Authority and the Israeli Birding Center joined leadership, bringing professional birders, surveyors, and a citizen science coordinator. The protocol changed to a fixed 10-minute count within 100 m, with no movement, in populated areas. A simple GIS-based online form was introduced, and by 2019, reporting moved to Hebrew-translated eBird. Data analysis included only protocol-compliant records. In 2019, Technion researchers used count data dating back to 2006 and paired it with parallel datasets to address earlier methodological gaps.

Phase 3 (2022–2024)

During this phase, the Israel Center for Citizen Science joined the project’s leadership. While the protocol and eBird platform remained in use, new tools such as R and OpenRefine were introduced for data analysis. The Center’s primary contribution focused on enhancing public engagement and broadening outreach efforts.

Increasing Project Visibility

Core outreach efforts over the years included upgrading the project website with clearer messaging, updated resources, results, and materials. A new bird ID guide was developed, focusing on distinguishing similar species—replacing a previous guide featuring only 19 common birds. Workshops, training sessions for educators, and preparatory events for families were held annually. The project was regularly promoted at conferences, in national media, newspapers, and social platforms. To address app adoption barriers, short instructional videos were produced for eBird, Merlin, and species identification tools.

Results

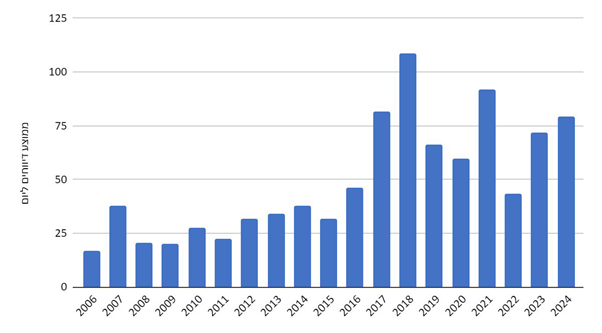

To evaluate educational and engagement goals, we assessed public participation levels and report submissions. Since count dates varied initially, we examined average reports per day rather than total reports (see figure). Public participation showed fluctuation rather than a steady upward trend despite outreach efforts. Participation rose until 2018—likely due to NPA’s promotional campaigns—then declined in 2018–2020, possibly due to difficulties using eBird. During COVID lockdowns, counts increased as people sought outdoor activities near home; remote education via Zoom also encouraged teacher-led home counts over classroom counts. In 2022, rainfall reduced average daily reports to below 50. In 2024, despite heavy rain, average daily reports rebounded following renewed outreach.

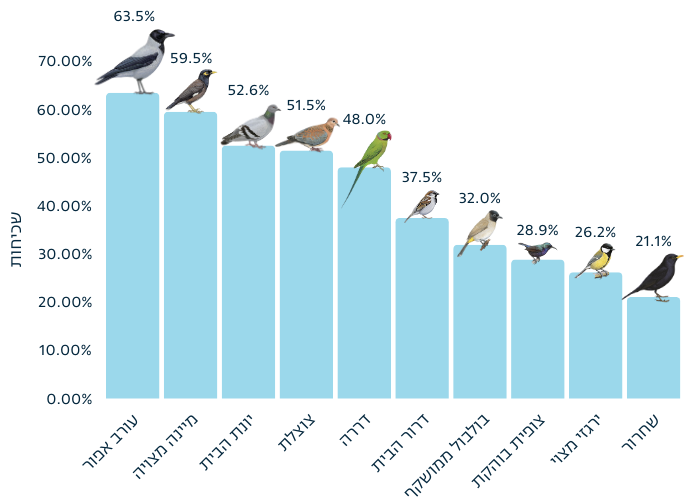

Scientifically, urban wild bird diversity declined, while invasive species—Common Myna, Collared Dove, Monk Parakeet—grew more frequent. In 2024, the Hooded Crow was the most observed species (>60% of reports), up from third place in 2006, followed by human-associated birds such as myna, dove, White-spectacled Bulbul, and collared dove. The House Sparrow, most common in 2006, fell to sixth in 2024. The myna moved from 30th (<10%) in 2006 to 2nd (~60%) in 2024. The collared dove rose from 15th (<20%) to 5th (46%).

Insights & Key Questions

Findings and questions that emerged from analyzing 19 years of project evolution:

- Participation levels vary year to year, with identifiable factors (eBird adoption, COVID lockdowns, rain).

- Accurate ID can challenge participants, suggesting the need for better species-distinction training.

- Weighing development, outreach, and educational investment: Are these efforts improving report quantity and quality?

- eBird usage clearly impacts report numbers—should the project revert to a simpler form-based method?

- Re-evaluate whether the protocol is optimal or needs adjustment, knowing that changes may impact ability to compare new vs. historical data.

- And critically: Is the project focused on scientific output or community education?

In an era of rapid biodiversity change, citizen science globally contributes crucial data that inform conservation policy and environmental decisions. To expand this data foundation in Israel, projects must be designed robustly and sustained over time. Our 19-year experience with the Bird Count offers seasoned insight into project life cycles and can help future citizen science leaders improve planning amidst changing conditions.

Recommendations for Long-Term Citizen Science Leaders

Expect and prepare for change: Long-term projects are inherently dynamic. Cultural and technological shifts should be anticipated from the start and incorporated into planning.

Detailed scientific planning: The scientific framework is critical. Protocols and data analysis methods should be carefully designed in advance based on clearly defined research questions developed in collaboration with subject-matter experts—and changes to these protocols should be avoided whenever possible.

Structured decision-making: Project decisions should be grounded in well-documented meetings between the core leadership and supporting teams (e.g., science, outreach, communications), both before and after each implementation phase. These records can guide future directions.

Effectiveness evaluation: To assess success, all actions taken must be systematically documented and reviewed. A clear evaluation mechanism should be in place to measure impact over time.

Featured image: Jonathan Ben-Simon, iNaturalist